Drs. Goodall and Dolittle, My Heroes

I have just had the rare privilege of spending an evening and the following morning with Dr. Jane Goodall, renowned primatologist, and her staff at the Aspen Ideas Festival. I volunteered to help in order to be in Jane’s presence and get a sense of just who this woman really is, a person I have admired for many years. My job consisted of sorting T-shirts, channeling people in the right direction for her book signing, and selling books. Menial labor in some sense—but each moment was precious to me.

I got to see first hand how this woman, who has captured the hearts and minds of millions all over the world, operates. She signs books for as long as it takes, sometimes up to four hours. After this lecture, we were finally packing up at nine o’clock at night, two hours after her talk ended. She still had a dinner to attend afterwards, and then needed to do some work on her next book, which is about nutrition. She later said that if you still want to eat food, don’t read the book! Among other things, she discusses the harmful effects of genetically modified food.

And there she was again the next morning, ready to go. This is evidently nothing unusual for her; at 71 years of age, she is on the road speaking 300 days a year. Dr. Jane, as she is often called, then participated in a panel discussion with Tom Lovejoy, a well-respected environmentalist.. The moderator began by quoting a paragraph from an article called, “End of the Wild” by Stephen Meyer. I had previously read that article and found it extremely depressing. The premise is, “The extinction crisis is over. We lost.” The question posed to Jane and Tom was: Is there really a reason for hope?

Both Jane and Tom seemed to agree that there is. They each shared numerous stories about species that were on the brink of extinction and were then brought back to life. Jane spoke of a species of bird with only one breeding pair remaining, and through the efforts of an extremely dedicated person, the species was saved by harvesting several clutches. She joked later that she had been one-upped by Tom, who shared about the very last surviving bird of a species similar to the mallard. Because this female carried semen within her body after her mate died, she was able to produce eggs and generate new life, resulting in thousands of birds now alive.

What touched me most? Jane’s deep connection to animals and the natural world, and her strong dedication to the conservation and protection of the ones she loves so dearly. A man asked her what causes her to be so calm, confident, and committed, those rare qualities that allow her to do what she does.. With deep reverence, she spoke about the peace of the forest. She said that all she needs to do is close her eyes and she is there. She carries it with her.

She talked about the beech tree in her backyard, as a child in England. It was not a particularly special tree, but she sat in that tree for hours, often reading Dr. Dolittle (a book by Hugh Lofting, about a doctor who talks to animals.) Jane said that Dr. Dolittle was a huge influence in her life, and that her childhood friends often told her that she could talk to animals. She said that even though she wanted to, she knew she couldn’t.

Here is where I beg to differ. I believe that Jane does talk to animals—not through words, perhaps—but through her deep love and appreciation for them, as well as through her dedication to their welfare and well-being. I am sure that intuitively she knows things the rest of us can’t even fathom.

I first met Jane Goodall in 1987. I was a recently graduated veterinarian then, doing a residency in zoo and wildlife medicine at University of California at Davis. One of my duties was to serve as veterinarian for the Sacramento Zoo, and during that time I attended a lecture which Jane gave at the zoo.

I was so excited to meet my hero! After waiting patiently–or not so patiently– in line to have a book signed by her, I told her that I had been to Africa and wanted to go back, and that I was doing a veterinary residency. I had just spent some time at the UC Davis Primate Center as part of my residency program and had also worked with chimps at the zoo. In fact, I had been with them when they were introduced into a brand new cage that was open, spacious and outdoors–a great improvement from the old cage, which had been a small and dingy concrete cave. I didn’t mention the fact that we needed to wear plastic garbage bags to visit the chimps because when they saw veterinarians coming they took the opportunity to fling unmentionable biological products at us.

I thought she would tell me how great I was, commend me for all the hard work I had done in my career, and encourage me to go back to Africa. Instead she told me that veterinarians were among the worst offenders in terms of animal abuse and exploitation because, although they are often in positions of power, they put up with the cruelty that goes on in the animal world without speaking out or changing things.

At first I was devastated, and then I got mad. I was thinking: “I am not like that. I am a good person. I love animals and do what is right by them. Who is she to tell me these things? What right does she have to judge veterinarians?”

So the next night I went back. Jane was again signing books after a private dinner put on by the zoo. When I met with her this time, I told her that she was wrong, that not all veterinarians are insensitive, that some of us really care. She apologized and said that perhaps she had generalized too much and was a bit too harsh.

Now, looking back on this, I see that she was right to some degree. Certainly not about all veterinarians–many are extremely dedicated to animal welfare. But I see how naïve I was back then, how accepting of the status quo without questioning it, and how afraid I was to speak up. Yes, I had worked at the primate center and the people seemed nice enough, but I see now that I wasn’t willing to experience my own feelings or to honestly look at what was being done to the animals. I didn’t have the courage or openness to look at the truth.

The truth was that there were abominable horrors going on in the name of science and I wasn’t able to acknowledge the reality of the situation. Some years earlier, in 1981, I had worked at the Oregon Regional Primate Research Center as a veterinary student, one of two chosen to spend a summer there. It was a great honor and I thought I was doing good work. But, in truth, it was extremely difficult emotionally for me to deal with the things that went on. In addition to experimental surgeries and even euthanasias, just the fact of having these intelligent, sensitive animals living in small metal cages was extremely disturbing. I will never forget the faces of those monkeys: some were filled with hate and anger, and others depressed. Our job was to care for their health– not their feelings.

Since that time, my career has taken a 180 degree turn. I was feeling dissatisfied with my work as a veterinarian, and so in 1992 I stopped practicing traditional veterinary medicine. I spent some years studying holistic medicine for animals. From there I began working as an animal communicator, someone who speaks telepathically with animals: Dr. Doolittle in the flesh.

What an amazing journey this has been! Trained as a scientist/doctor, and possessing a well-trained analytical mind has made it extremely challenging for me to believe that what I am now doing is real. In fact, for some years I didn’t tell most people what I did. I simply said, “I am a veterinarian who specializes in emotional and behavioral issues of animals.”

As I gained experience and confidence by working professionally as an animal communicator, I learned to trust myself more and more. Once, as I was just getting started, I worked with a dog, a Miniature Pinscher named Rudy, who helped me in this direction. Rudy was peeing all over the house, ruining drapes and bedspreads. Dorothy, Rudy’s person, was about to find Rudy a new home, out of sheer frustration. At her request, I talked with Rudy. It was incredible. I learned that he resented Dorothy’s new husband, Tom, who had taken over his position as “man of the house,” and that he was downright “pissed off” at him. What made matters worse was that Tom sprayed Rudy with a water bottle each time he urinated in the house, so it felt to Rudy like Tom was marking his territory—stimulating Rudy to mark his all the more.

I told Rudy that he had better shape up or he would be shipped out! No more fooling around. I asked Dorothy and Tom talk with him as well, acknowledging him as a member of the family and letting him know he was loved. Immediately after that session, he stopped peeing in the house.

After that, there were many other examples that proved to me that I did indeed seem to be able to communicate with animals. A horse named Farah, who was about to be euthanized because of a terribly infected leg, instead healed after several conversations. Sometimes animals would share with me a certain emotion that I later discovered was exactly what the person was dealing with. I learned that our companion animals are constantly supporting and loving us, and often taking on our “stuff,” attempting to take it from us and help us heal. I worked with a lot of animals who were on the brink of dying and found that I was able to help them and their people deal with the most difficult and yet most precious period of their lives together.

After a few years, I traveled throughout the country, speaking about interspecies communication and teaching workshops. As I shared my stories with people, they shared theirs with me. Sometimes they had not told anyone about their amazing experiences because they were afraid of being laughed at or criticized. I remember a young woman biologist in Costa Rica. I had gone there to swim with dolphins and her job was to monitor the boats. She confided in me that she always knew just where the dolphins would be because the dolphins came to her in her dreams at night and showed her. She had told her major professor at the university about this and he had told her never, ever to mention this to anyone: they would think she was crazy and it could hurt her career. She seemed relieved that, at last, someone believed her.

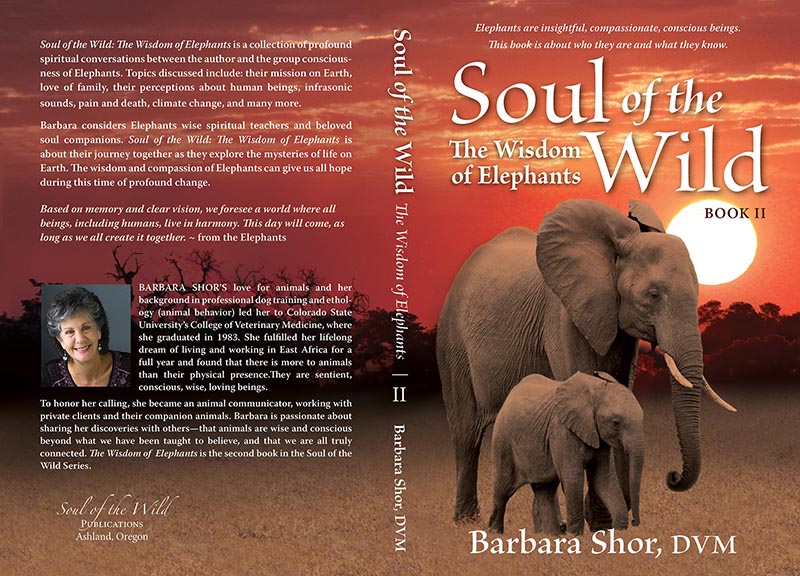

After working with domestic animals for a few years, I began communicating with the wild ones, which is my true passion. I am now completing the first in a series of books entitled Soul of the Wild. The first book consists of deep, soul-level messages from both elephants and whales. They speak about who they are, what they feel and know, and what they see in us, as human beings. They also give suggestions about how we can create a better world where all species, including human beings, might live in harmony. In future books I intend to address a variety of other species.

People have asked me, “Why elephants and whales?” The truth is that they came to me, not the other way around. After my last trip to Africa three years ago, I felt the elephants’ presence with me very strongly and that is when the conversations for this book began. The whales came later, after I had already been working with the elephants for several months.

As I have communicated with both species, I see that elephants, the largest land mammals, and whales, the largest marine mammals, have a great deal in common, including their sociability and low frequency sounds. They also seem to share a spiritual function on the earth, which is to energetically impart peace and harmony to this beautiful planet: the whales in the oceans and the elephants on the land.

And so, after this long and exciting journey I’ve taken with the animals of this world, it is clear to me that animals do talk and that we can communicate with them. Dr. Dolittle is not as far-fetched as some believe, at least in my opinion. And Dr. Goodall is not so far from Dr. Doolittle as she may think. Indeed, I feel that Dr. Doolittle’s legacy is alive and well in many more of us than some would believe.

Published in 2005 in the Post Independent, Glenwood Springs, Colorado